In line with the 2022 theme of the International Women’s Day, let us all continue to “break the bias” wherever we find ourselves, in all ramification of our medical profession and beyond ~ A.O.A.M 2022

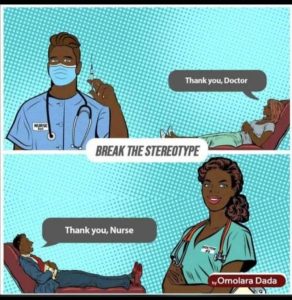

I remember being referred to as “nurse” on countless occasions during my days in medical school and this always got me thinking to myself. To the extent that, I couldn’t wait to become a doctor so I wouldn’t have to deal with that anymore. Well, it turns out I assumed wrong.

The other day, I spoke to some female colleagues currently undergoing their housemanship at different centres across Nigeria and they all confirmed that they still experience this same scenario in their places of work. They agreed that it was annoying and somewhat embarrassing to be doing all that work only to be addressed by a wrong title. One of them who works in Northern Nigeria particularly said that it was commonplace there for people to assume all male medical personnel were doctors and all female medical personnel – nurses; even when they were adorned in their ward coats or carrying name tags.

This role-or-credential questioning behaviour commonly exhibited by patients and their relatives is one of the many microaggressions in Medicine. Others include demeaning comments, non-verbal disrespect, rejection of care, generalization of social identity.

Microaggressions are behaviours that stem from implicit bias-unconscious stereotypes, assumptions, and beliefs held about an individual’s identity. Microaggressions and implicit bias may be encountered throughout medical training and clinical practice in interactions with colleagues, superiors, patients, and patient’s families.

It would interest you to know that these microaggressions are not limited to Nigeria alone. Infact, the other day, while scrolling through Twitter, I came across a thread by a female American physician narrating how she had admitted and reviewed a patient, introduced herself appropriately, gotten their history and conducted a full physical exam, even discussed her treatment plan with the patient and answered their questions; only to receive an urgent page from a nurse hours later informing her that the family was upset that no doctor had attended to them since the patient got admitted. Crazy, isn’t it? Several comments from female doctors all over the world reiterated similar experiences.

Although these biases may be unconscious and unintentional, the negative impacts on physical, mental, and emotional well-being are notable. Current data support that female medical students and doctors who experience microaggressions are more likely to report associated symptoms of burnout and depression. Subjection to persistent bias can create feelings of invisibility and exclusion for the recipients, and frequent questioning of an individual’s qualifications based on identity can lower productivity. In the long run, a stressful and hostile work or learning environment is created.

While it is not very difficult to guess why this happens, I thought it necessary to find out the individual opinions of my colleagues on the issue. Therefore, I will be exploring the reasons suggested for such biases against women in Medicine and key strategies on how they can earn the recognition and respect they deserve.

The role of women in Nigeria and the world at large varies according to religious, cultural, and geographic factors. Many cultures see women solely as mothers, sisters, daughters, and wives; and not as leaders, career persons, or pacesetters. This is because these traditional gender roles usually place women at subordinate positions compared to men, people have been conditioned to think that professions that are demanding (both mentally and physically)-such as Medicine are to be reserved for the male folk only. It is the same reason why a male Nurse is first regarded as a doctor before anything else. Unfortunately, despite modern-day advancements and the opposition of these outdated societal norms, many individuals are still holding on to beliefs regarding gender stereotypes.

To correct this age-long belief, there needs to be a total and continuous re-orientation of the people, beginning from the grass-roots. More awareness needs to be created in communities and schools through public enlightenment campaigns with the goal of emphasizing that anybody could be anything they want to be irrespective of their gender. This will enable a demand for structural accountability. However, there must be a willingness by the people to engage in these difficult, uncomfortable conversations and a readiness for growth.

Representation of medical personnel’s in various media channels should also be more inclusive of the female gender. If more women are displayed as doctors in movies, television adverts, and educational books or novels, slowly but surely, people will start getting used to the idea of women in Medicine and soon be able to let go of these gender stereotypes.

Making appropriate and specific uniforms available to be worn by women in Medicine could also help in ensuring that they are adequately recognized. The white gowns worn by female medical students in a good number of medical schools in Nigeria (particularly in South-Eastern states) are often counter-productive. Obviously, you cannot keep correcting the impression that you are nurses when you are dressed exactly like them. Ward coats should be used as a general rule instead. Women in Medicine can also employ the use of name tags with their titles boldly written to reduce the number of times they are addressed wrongly.

Implicit bias and microaggressions training and policies should be incorporated into medical education and resident curriculums. Equipping medical students, trainees and healthcare providers with the tools needed to recognize and handle microaggressions when witnessed or experienced demonstrates systemic level accountability and communicates the importance of the issue.

Microaggressions may have a covert nature but its detrimental effects are tangible and far-reaching. As providers, we must strive to understand and expose the many ways prejudice manifests within medical training and clinical practice. It is our obligation to confront these biases to promote a safer and more inclusive medical community and workforce.

About Author:

Onodu Prevail Chibuzo is a Medical Doctor with an interest in medical research. She is an avid reader, a creative content writer, and a yogini. She believes that hardwork, consistency, and a strong willpower are keys to a successful life. She writes from Enugu, Nigeria. She can be contacted on both Twitter and IG @Vailyy